Pinning Her Hopes

November 5, 2018

Snowpocalypse

November 5, 2018

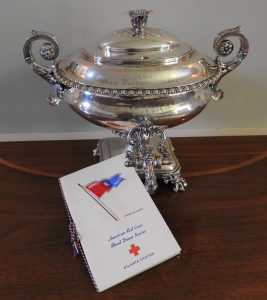

Glancing through the number of times May Patterson Goodrum Abreu was mentioned in the Atlanta Journal Constitution for entertaining in her Shutze-designed home on West Paces Ferry Road, one might assume she was merely a typical society matron of her time, concerned with debutante balls, high teas, and dinner parties. Although little personal ephemera from May’s life survives in our collection, a few items hint at a more complex woman than is revealed in the newspaper articles. The items she saved, including the program and acceptance speech for a Red Cross Award, and a nineteenth-century sterling silver urn engraved with the words “Atlanta’s Woman of the Year/1943/May Patterson Abreu”, tell a deeper story—one of her support of the war efforts during World War II and her pride in a job well done.

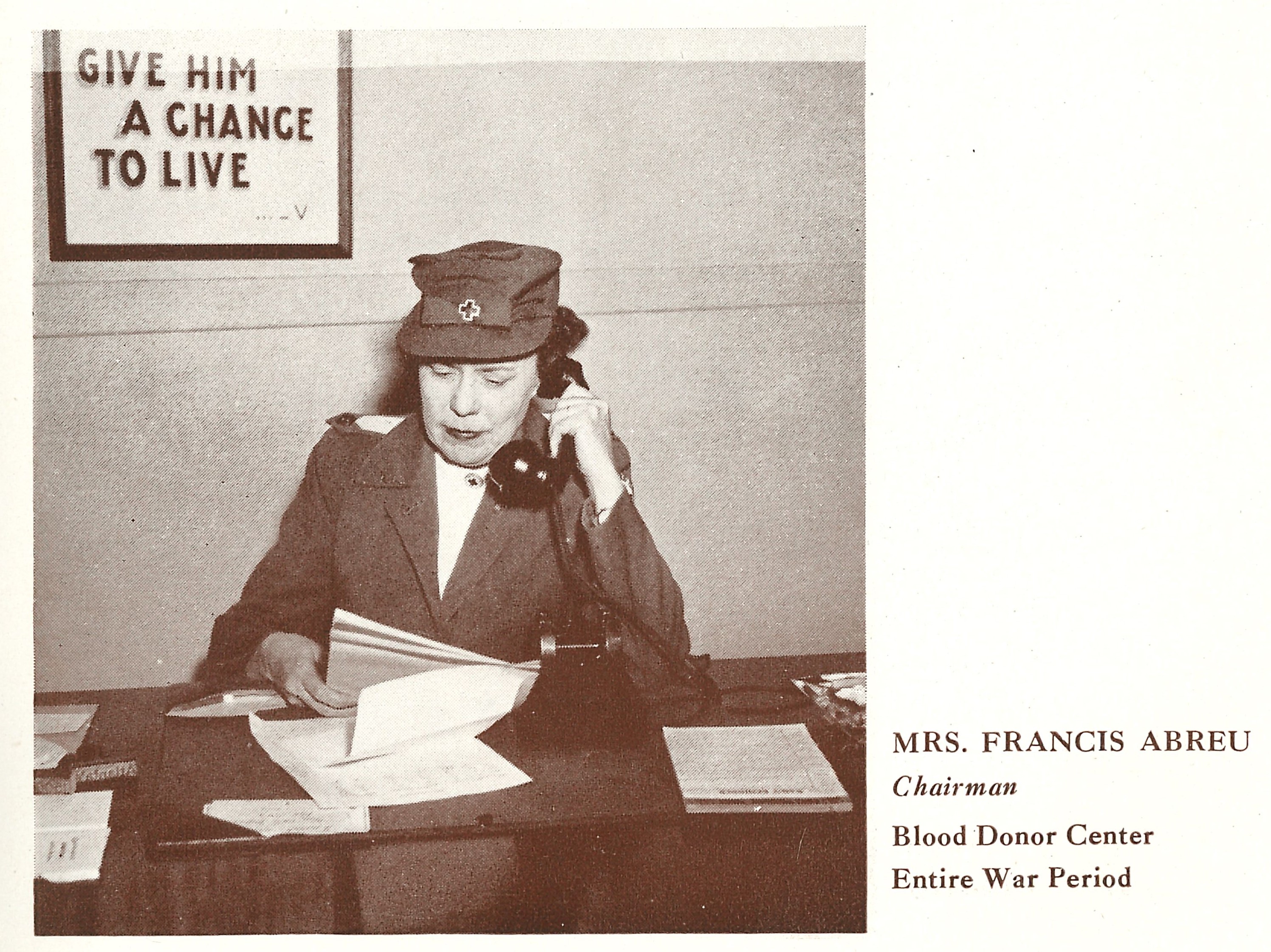

Dorothy Haverty Grove recorded the major efforts of the Red Cross activities in the Historical Record of the Atlanta Chapter American Red Cross in World War II: September 1, 1939 – July 1, 1945 (published 1948). In March 1943, a new Blood Donor Center opened at 291 Peachtree Street, NE, and May was named Director. The volunteer job was full time one – five and a half days a week—though this was probably not dissimilar to her younger days spent working the retail counter of Jacob’s Pharmacy. Dorothy described the center as a “quiet, cheerful establishment” run “as perfectly as any complicated business, with a difference of an added personal element.” May directed the campaign to recruit donors like an army officer. The demand for dry plasma for injured servicemen was high. The Red Cross requested donations be stepped up from 1,000 per month to 6,000 per month. Through May’s society connections, she solicited the National Daughters of the American Revolution Fund for a Mobile Unit which enabled the program to operate within a 75-mile radius of Atlanta. Not unlike today’s corporate sponsorships, she approached businesses to donate as groups: the Atlanta Federation of Trades, soldier-students of the Atlanta Ordnance Depot at Fort Benning, and the employees of the Constitution and the Atlanta Journal, to name but a few. In Dorothy’s words, “Walnut 9635 became Atlanta’s most important telephone number—all calls making dates for donors.” That year, May, Mrs. Robert C. Hunt and Mrs. J. B. Suttles attended the two-day conference of the Blood Bank Meet in Chicago. May called on every advantage she could employ for a successful outcome.

The success of the Atlanta center and May’s leadership abilities came to the attention of the War Department. So efficiently run under May’s direction, the center was awarded the highest honor of the Army-Navy “E” Award for two consecutive years. Her efforts had resulted in 90,442 registered donors, 30,346 through the Mobile unit, and a total contribution of over 150,000 pints of blood. Throughout the years, she saved her typed and annotated acceptance speech, poignantly expressing her belief in Allied victory and a soldier’s return to a life swept off course by war.

That same year, a committee of fourteen women was established under the direction of Charles H. Jagel to select seven women of Atlanta who had made outstanding contributions to their community. May was selected as both the Woman of the Year in War Effort and Atlanta’s Woman of the Year. The January 22, 1944 Atlanta Constitution article, accompanied by a photograph of May wearing a simple short-sleeved dress with a wide lace collar and accessorized with modest pearl and diamond earrings accepting the urn from Georgia’s First Lady, boasted “City’s Woman of the Year Is Mrs. Francis L. Abreu.” The article describes May characterizing herself as “a hum-drum woman with a one-track mind.” Attended by hundreds of prominent Atlantans, the dinner at the Biltmore Hotel must have been a milestone in May’s life; a girl who grew up in the rough and tumble, blue-collar Castleberry Hill area at the turn of the century, likely never finished high school, financially supported herself and her aging mother for years, and was considered an undesirable spinster in 1926 when, at the age of thirty-five, she married one of Atlanta’s wealthy eligible bachelors.

But perhaps it was that very hand of cards she’d been dealt early in life which made her uniquely qualified for the task at hand during World War II. Oral histories tell the story of a woman who was deeply altruistic and identified with less-fortunate souls throughout her lifetime. Nine mutts from the local humane society had the run of her 6-acre property and mansion. She generously sent two children of her staff to college, and purchased a home, car, and Coca-Cola stock for the retirement of two beloved staff members who cared for her until her death in 1976. It seems May was a woman who heeded the call to action throughout her lifetime.