Snowpocalypse

November 5, 2018

A Classic Duo

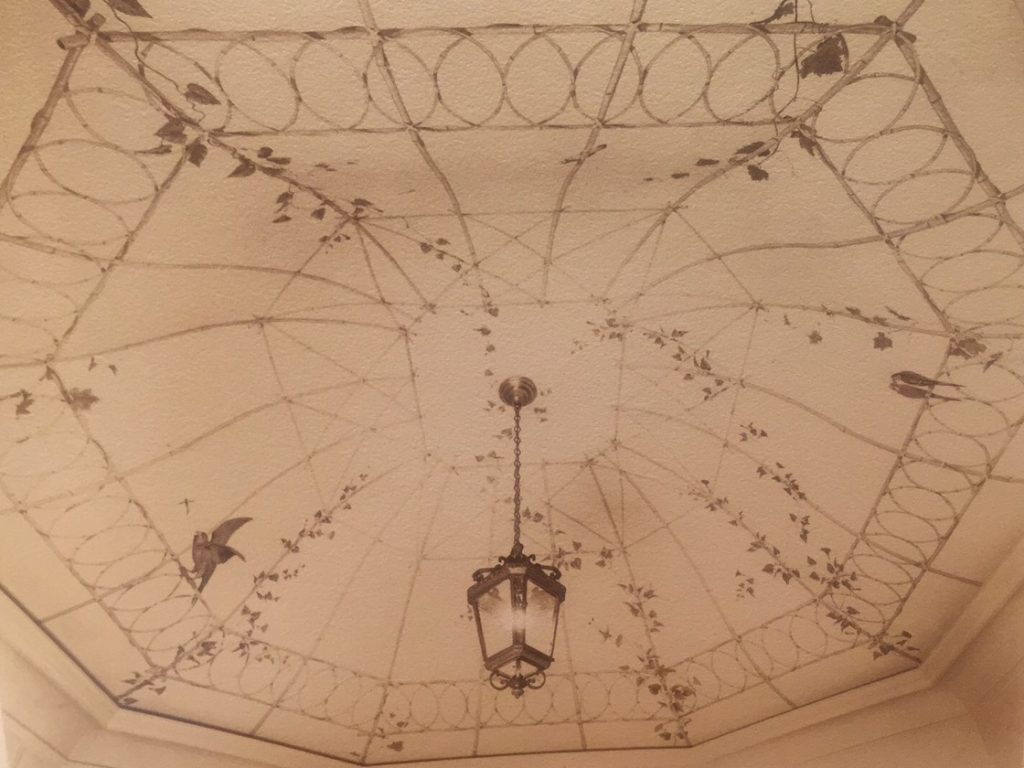

November 6, 2018When I came on board this project in February 2016, the looming light at the end of the Goodrum House restoration tunnel was the well-known Menaboni Breakfast room. In 1930, Philip Trammell Shutze designed an intimate casual dining space for May Goodrum and her mother, Mollie. A 10’ x 10’ octagonal room tucked between the kitchen and a lady’s powder room at the front of the house, it incorporated shelved niches in four corners and an ogee shaped ceiling. The room was described in the October 1932 issue of House & Garden as “suggesting an airy birdcage with its rattan motifs and soft Chinese coloring”. The article further describes the golden niches with brightly colored figures of Chinese caricatures. What lay before me was a far cry from the description in that 1932 magazine article.

The initial meeting between Shutze and Athos Menaboni, the artist who created this tiny gem of a room, is lost to us. What we do know is that Athos immigrated from Italy in 1921, residing in New York City before making his way to Tampa, Florida to work as an art director illustrating real estate ads during the 1920s Florida land boom. With the land bust in the late 1920s, Athos headed north to Atlanta, Georgia. Recent research indicates he might have been acquainted with Allyn Cox, another important artist who created the dining room murals at Goodrum House in an Asian motif. Cox and Shutze were close friends from their youthful days at the American Academy in Rome. It’s possible Cox supplied Athos with a letter of introduction to Shutze. By whatever means the initial meeting took place, Shutze had the perfect room to compliment Athos’s talents.

What Menaboni envisioned at Goodrum House was a charming aviary filled with colorful flitting birds: two lovebirds cuddling on the bamboo lattice, a parrot chasing down dragonfly, and an exotic hummingbird with peacock-like tail feathers to name a few. Intertwined between the lattice, insects, and birds were vines of grapes, blue and pink morning glories, and ivy. Menaboni returned to his Italian roots in the niches, but with a twist and nod to Allyn Cox’s Asian-inspired dining room conceit. Athos gilded the niches and oval-shaped paintings above with gold leaf harkened back to the gold-ground panel paintings and altarpieces he studied in his youth, but the similarities stopped there. He put his good humor to use on this glowing surface by painting whimsical scenes of Asian caricatures in slap-stick comic situations: a mischievous monkey grabbing a man’s braided ponytail, another flinging cocoanuts at an unsuspecting passerby, a baby being scolded by his mother for playing with a tiny cannon. While the comic strip-like niches incite giggles, the oval panels above reveal Athos’s depth of talent in beautifully composed and modeled still-lifes: a bowl of plums with an unusual pipe, a vase of delicate cherry blossoms arranged with an eye for Asian aesthetics, a box wrapped in impressively convincing drapery. May’s breakfast room enticed the visitor to spend time looking closely at their environment.

But eighty-seven years had taken their toll. Layers of paint, years of repeated cleaning and wiping of the niches, and severe water damage had left the room in a mournful state. Restoration attempts in 1984 and the early 1990s had made major changes to the artist’s original intent. When pipes burst a second time in the south wall of the room releasing steam directly onto the plaster ceiling, white latex paint applied to the mural background was thought to be the best solution. By 2009, portions of the painted ceiling were separating from the substrate, the gold ground of the niches were dulled by years of nicotine and harsh cleaning, and fluctuations in temperature and humidity had caused paint to flake off the tiny gilded vignettes. This project was saved for last simply because there were many difficult curatorial and restoration decisions to be made.

By Fall 2017 the time had arrived to tackle those decisions. Chip Miller and Steve Tillander of Restoration Craftsmen, Atlanta, Georgia started by photographing every inch of the ceiling. Steve had experience with restoring other Menaboni murals. He has an eye for Menaboni’s original brushstrokes. The first question was if removal of the white oil paint was possible. Chip came up with a solution to remove the paint and subsequent layer of varnish found underneath. While Steve started working on paint removal, Chip worked on adhering the areas of the mural that had separated from the plaster substrate. He devised a paper hinge method to keep the hanging chads in place while applying adhesive behind it, activating it with a warm heating iron, and consolidating the area to the plaster. Areas of the mural were missing and required inpainting. Armed with a stack of photos spanning between the 1930 and 1984 and a digital projector, Steve carefully recreated the lost sections. Paint analysis revealed the original color of the walls was a lighter blue than its current state. The walls and trim were stripped of eighteen layers of paint and returned to their original blue. By Christmas 2017 the room was finished, but the niches were still dull and the vignettes muddy.

Larry Shutts of Savant and Shutts Art Conservation, Atlanta, Georgia cleaned a few test spots on the oil-painted caricatures. He felt the painted areas could benefit from a light cleaning, but the gilding might be problematic—but Menaboni had utilized the gold leaf in his highlighting and modeling the figures. As Larry cleaned away the years of grim, details and textures of the figures’ clothing, the pink skin tones of the babies, and Menaboni’s painterly brushstrokes came to the surface. He contemplated what he could do with the gilding. It was holding up to a light cleaning around the figures and the shine was returning. He decided to test a small area; a fox-like creature running through a forest, and then a larger tiger stalking a man wielding a hatchet and using his coolie hat as a shield. The gold still cast its glow. By slightly changing his technique, Larry could clean the gilding and protect it with a light coating of varnish. The gilding in some niches is thinner than others and shows more wear. Re-gilding without damaging the delicate paintings isn’t possible at this time. The inpainting of the slight flaking paint on some figures made all the difference. I’ve looked at these muted paintings with areas of loss for so long, it was slightly shocking to see them in their nearly original state. The viewer’s eye is no longer distracted by breaks in the color field within the scenes and Menaboni’s virtuosity with a paintbrush shines through.

Questions still remain—the space is small and doesn’t lend itself easily to tours. What do we do about the original arrangement of furniture? Maybe a chest and mirror against the south wall and forgo the drop leaf table? The carpentry of the walnut floor is exquisite, but May had a needlepoint carpet to compliment the apricot taffeta curtains. And speaking of those apricot silk taffeta curtains, would she lean toward a pinkish-orange toned apricot? Or an orange-yellowish tone? A plain lustrous taffeta? Or one with a delicious water silk pattern woven throughout? The endless questions continue as Menaboni’s birds burst into song once again.