Why the Caged Bird Sings

November 5, 2018‘So far I find Shutze the most interesting of the men I didn’t know before I came here. He is not at all what you would think from his name and comes from Atlanta. Incidentally, he is a very clever architect, and is the only person who has sense enough to appreciate my rococo Cantigalli vase. Everyone else has pure taste and is scared by the yellow flowers and curly handles.’

I am happiest when digging in boxes in an archive like a bloodhound on the scent of a trail. I hit the jackpot last year at the Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C.—almost 170 letters written by Philip Trammell Shutze, the architect of Goodrum House, to Allyn Cox, the painter of the dining room murals. A quick trip to the Atlanta History Center in Atlanta, Georgia yielded almost another 230 letters from Allyn to Philip. The extant correspondence starts in the 1930s, but the bulk of the letters are from the period between 1940-1980. Not only were their letters kept, but Allyn and his family preserved his European correspondence between 1916-1920 during his sojourn at the American Academy in Rome, Italy. It was there on the highest hilltop in Rome, the Janiculum, that Allyn and Philip met.

Born in 1896 to Kenyon and Louise Cox, Allyn seemed destined to follow in his parents’ artistic footsteps. Classically trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris between 1877 and 1882, Kenyon Cox returned to the United States and established himself as a prominent American painter, art instructor, and critic. Louise was one of his art students while attending the Art Students League in New York in the mid-1880s. They married in 1892 and together nurtured three talented children: Leonard, an architect, Allyn, a mural painter, and Caroline who found her creative stride in landscape painting later in life after the death of her husband. But it was Allyn who showed the most promise in pursuing painting as a professional career. At the encouragement of his parents (Kenyon frequently sat on the jury for the Academy), Allyn competed for and won the Prix de Rome in Painting in 1916 which provided him with the opportunity to study in Italy for three years, along with a much-needed stipend of $1,000 per year, a free room, and a studio.

By the time Allyn arrived in Rome in October 1916 Philip had one year of Academy life under his belt, having won the Prix de Rome in Architecture the year prior. In Allyn’s numerous letters to his family, he expressed dismay at the lack of discipline of his colleagues, the inadequate accommodations, and the perceived disinterest on the part of the administration to provide more rigorous learning opportunities. He wrote to his father of his self-consciousness and his inability to relate to the other men at the Academy, who he surmised considered him to be ‘a sheer freak.’ In short, he was disillusioned and terribly homesick.

His first mention of Philip was in a letter to his brother Leonard in November 1916. Following a description of the requirements to become a Fellow of Architecture at the Academy (and the mention of Leonard’s complete lack of qualifications in every regard) he described Phillip as 'perhaps more interesting as a person than an architect.’ The following month he wrote his mother:

‘So far I find Shutze the most interesting of the men I didn’t know before I came here. He is not at all what you would think from his name and comes from Atlanta. Incidentally, he is a very clever architect, and is the only person who has sense enough to appreciate my rococo Cantigalli vase. Everyone else has pure taste and is scared by the yellow flowers and curly handles.’

In Philip, Allyn found a kindred spirit; someone who appreciated the emotional and fanciful Baroque and Rococo styles over the preferred, staid, and Academy-endorsed Italian Renaissance. Philip was more serious-minded about the opportunity the Academy afforded him and soaked up his Roman surroundings. His sketchbooks reveal his full-hearted pursuit of the tenants of the Academy training—detailed, measured, and scaled drawings of ancient and Renaissance buildings, gardens, fountains, and decorative objects. He created scrapbooks of numerous photographs of decorative details from which he would draw inspiration throughout his career. He was also a great admirer of Kenyon’s writings, particularly Kenyon’s criticism of that hotbed of degenerate ‘Modern Art’ and the lamentation of the movement away from the tradition École des Beaux-Arts artistic training seeped in its reverence for Greek, Roman, and Italian Renaissance antecedents. Both Allyn and Philip believed professional artists and architects needed a thorough understanding of Classical art and architecture achieved only through a deep and prolonged study of its elements before having the temerity to rendering it asunder. They were summarily and straight to the bone Classicists. It was their calling in life to create and promote their arts through the lens of Classical aesthetics, taste, and beauty.

Not only were they die-hard Classicists, but on the surface, it would appear they were born a generation too late with the rise of Modern art and architecture. Allyn returned home to New York in 1920 and found work as a decorative muralist, supporting himself and his new wife with domestic commissions like the foyer of One Sutton Place for Mrs. Vanderbilt and the entry hall and ballroom in Trygveson, the Calhoun Mansion in Atlanta, Georgia designed by Phillip and inspired by three Italian villas studied during his years in Italy.

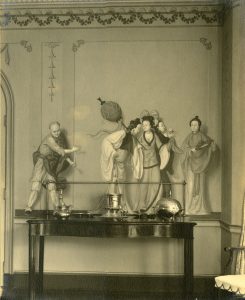

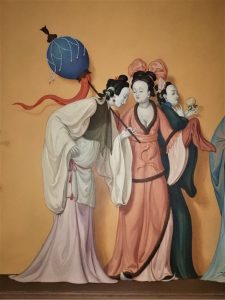

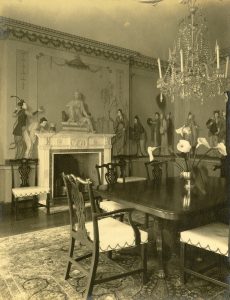

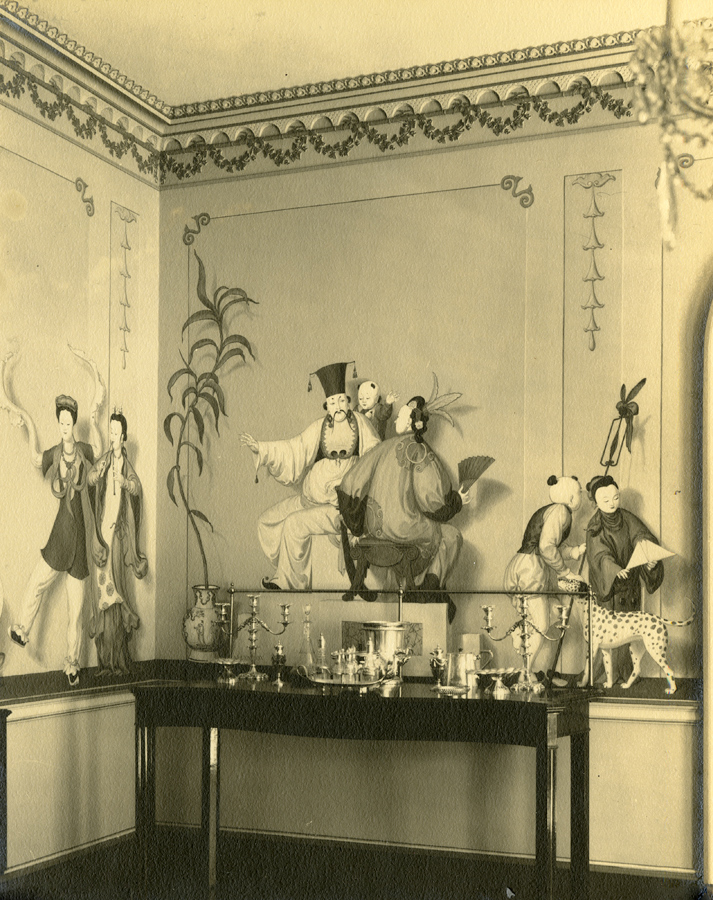

By 1926, Philip had established his career in Atlanta, becoming a partner in the architectural firm of Hentz, Adler & Shutze. Throughout his letters, Allyn often implored Philip to find work for him with his clients. He had reason to called on Allyn in 1929 to create a dramatic dining room setting in May Goodrum’s mansion on West Paces Ferry Road. Allyn composed a procession of Asian-inspired characters illustrated in a riot of colors: pinks ranging from pale to deep wine, cool lavenders to plum, aqua to cobalt blue, and grass to emerald green all against a background of mustard gold yellow. The range of figures, from the Thai Buddha who presides over the scene from her throne atop the fireplace to the figure of the Emperor with his heir apparent riding piggyback while a Dalmatian dog looks on, begs the visitor to look more closely at the details: the subtly blended modulations of lilac, lavender, and aqua brushstrokes highlighted with the faintest of pinks to create the modeling of Buddha’s legs, or the masterfully painted shadows of the potted orange tree that seem to move with the sunlight as it crosses the dining room walls throughout the day. To top it off, Philip designed a plaster cornice frieze of decorative arches surfaced with a pattern of fish scales, and bamboo entwined with ivy to harmonize with the paintings below. It is a never-ending buffet of visual delights of which one never tires.

While no correspondence exists of the initial planning of the Goodrum project, throughout the years Phillip and Allyn often referred nostalgically to their collaboration on the dining room and their desire to repeat the partnership. By 1949 there was discussion of Allyn returning to Atlanta to supervise a cleaning and restoration of the murals, but it never came to fruition. Allyn eventually won the long-term commission for continued work on Rotunda and corridors of the Capitol, and the George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Washington, D.C. His mediums varied from traditional plaster frescos to mosaics and stained-glass. Philip had a successful career designing upscale homes, hospitals, banks, schools, and commercial buildings throughout Georgia and South Carolina.

Over the next three decades, Allyn and Philip shared thoughts on a variety of subjects: the state of contemporary art and architecture, politics, art books and novels, antiques, gardening, trips abroad, bits of professional gossip, deaths of family, friends, and colleagues, and the ups and downs of their professional careers. In 1956, Allyn wrote, ‘I got to thinking the other day, and it came over me that we have known each other for forty years (1916 I went to the Academy in Rome) è formidabile! Also that we have really done so many of the things we planned + talked about in those days, in spite of wars and a changing world. We must have very strong characters, when I think that we have both got away with not swimming with the current all these years, and not done so badly, either of us.’

Throughout sixty-six years, they were each other’s champions, encouraging and supporting one another through the ebb and flow of life. As Philip poignantly once wrote, ‘In any event you have long proved a friend and in many instances, what seemed to be crises have somehow melted away, in no small way abetted by kind words from you.’ Allyn passed away in September 1982 and Philip followed three weeks later.