Watson-Brown Foundation (2008 – Present)

December 20, 2008

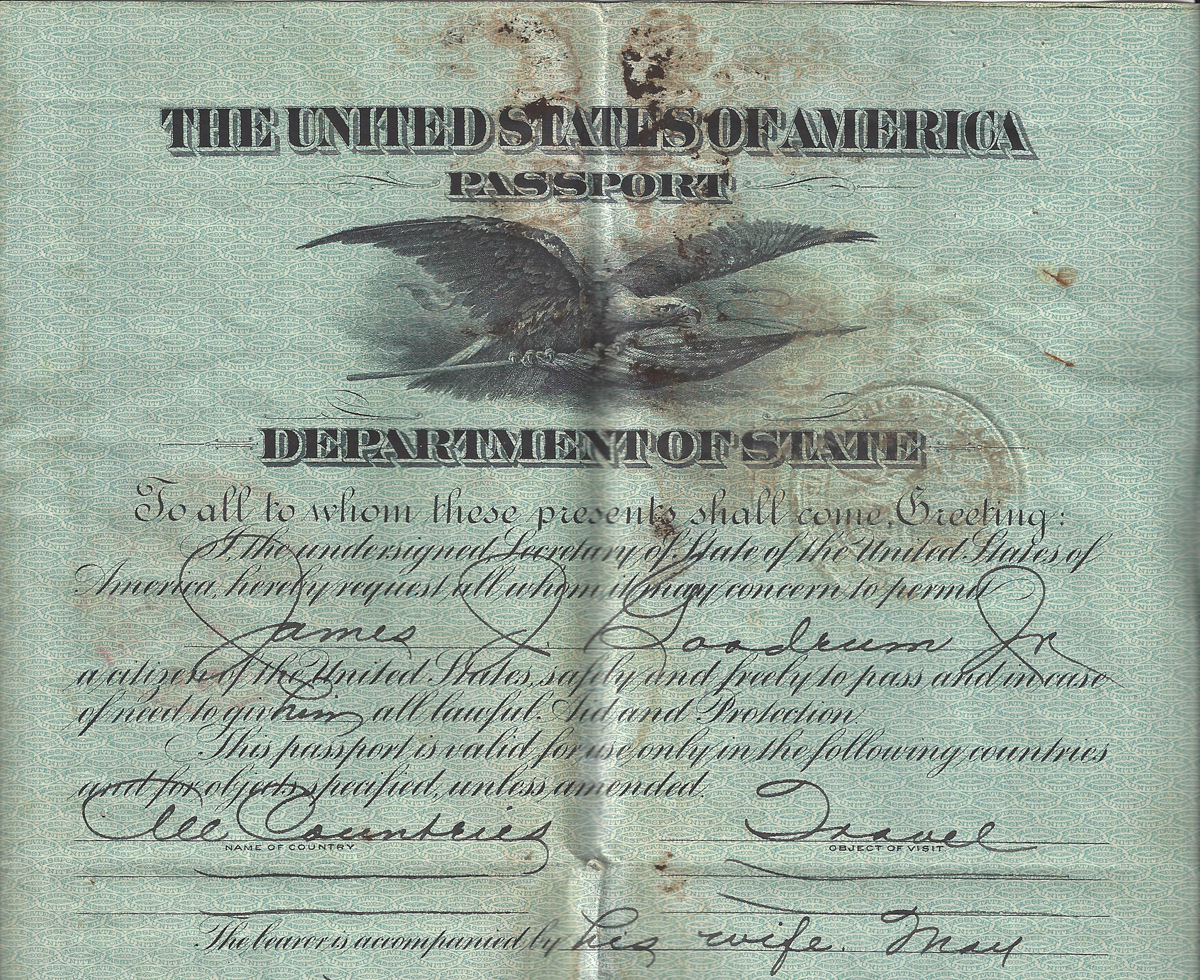

Passport

December 7, 2017-

Philip Trammell Shutze papers, MSS 439, James G. Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center

What do May Patterson Goodrum, Atlanta’s 1943 Woman of the Year, and woodworking craftsman Shawn Smart from Trinidad have in common? A love of beautiful objects! When May began furnishing her newly-built English Regency style Buckhead mansion in 1930, she turned to Edith Hills, a prominent Atlanta interior decorator, for advice. Edith, with her wonderful eye for stately English antiques, steered May toward an eclectic combination of Chippendale and Hepplewhite furniture, Asian objets d’art, and flourishes of French Rococo-inspired lighting fixtures. Yet today, not all of May’s collection, many items of which were purchased on jaunts with family and friends around the world, survives intact in Goodrum House. Some pieces, like the three-tiered crystal chandelier and foyer wall sconces, were still in the house when it was purchased by the Watson-Brown Foundation in 2009, while others are still owned by members of the Abreu family, and still others were simply lost. Luckily, the home was photographed for Architecture magazine in 1932, preserving May and Edith’s original design decisions.

Eighty years later, Shawn Smart entered the scene. A native of Trinidad with what he calls a “God-given passion for woodcarving,” Sean was inspired by the traditional carpentry techniques used in the British Colonial homes of his native island. Today, he is working as the lead carpenter on the restoration of Goodrum House. Armed with his personal collection of 450 antique English chisels, Smart works just as woodcarvers have for centuries. Among other projects throughout the house, Smart carved two new sconces for the foyer to match the two surviving fixtures, which, as we know from the Architecture magazine photographs, had originally been part of a set of four. After measuring the extant sconces, Smart produced detailed drawings of both the right and left originals and then transferred the designs to single blocks of African mahogany wood using a carbon transfer method. The next step was the painstaking process of carving the pieces themselves. In his soft Carribbean lilt, he relates why he chose to use this particular material. “I chose it because it’s a really durable wood and for its ability to hold fine details. These sconces should last forever, whether they’re used inside or out.” When asked how many hours he put in to producing these two objects, he said “I don’t know! I tried to keep track, but I should have been better about it!” Shawn’s examination of the sconces also yielded some clues about how the originals were produced. “Each carver has his own signature, like handwriting. I could tell that even though these two sconces look identical, they are not. They were definitely carved by two different hands. There was no machine work done on these.” The rich gold patina finishing the works will be left to Chip Miller and Steve Tillander, conservators with Restoration Craftsmen. “We’ll use a special gold powder paint typically used to finish burial caskets” says Chip. “It will perfectly match the coloration on the two original sconces.”

While Smart is currently working on the pavilion at Goodrum House, he continues to pursue his own artistic projects, producing large scale high-relief carvings. “I like to call myself a craftsman instead of a carpenter,” he states. In bringing Goodrum House back to life, the Watson-Brown Foundation is thrilled to work with extraordinary specialists like Smart, whose dedication to understanding the decorative arts of the past help recreate a world we now know only in photographs, preserving May Goodrum’s vision for sophisticated living for generations to come.